Italian food is commonly presented as a unified culinary system, both in popular discourse and in much of its global representation. This apparent unity, however, is the result of a historical and cultural construction rather than an accurate reflection of how food practices developed on the Italian peninsula. What is usually described as “Italian cuisine” is, in fact, a composite of regional, local, and situational traditions that resist being reduced to a single, coherent canon.

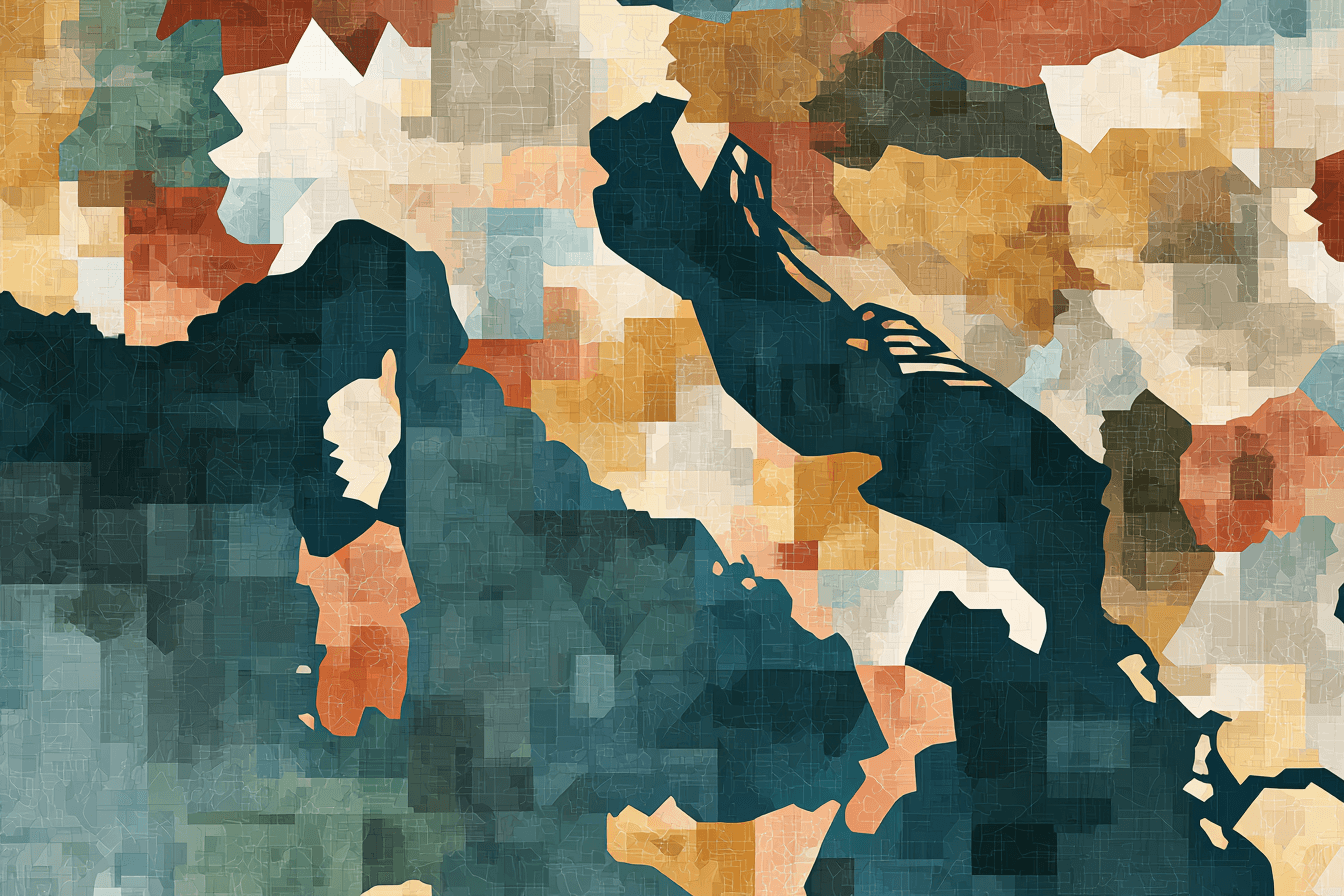

This plurality is not incidental. It is rooted in structural conditions that have shaped food production and consumption in Italy over centuries. Among these conditions, biodiversity plays a central role. Italy is characterized by an exceptional diversity of edible plant varieties, animal breeds, and localized agricultural practices. This diversity is not merely biological, but cultural, as ingredients acquire meaning through their integration into specific local histories, economies, and habits. As a consequence, culinary practices emerge from environmental and social specificity rather than from any nationally standardized repertoire.

The absence of a unified Italian culinary canon is further reinforced by historical patterns of political and cultural fragmentation. Unlike culinary traditions that developed around centralized courts or strong state institutions, Italian food evolved within a mosaic of regional systems that remained relatively autonomous well into the modern period. As scholars such as Massimo Montanari have observed, the notion of a unified Italian cuisine is largely retrospective, taking shape after political unification and gaining strength through discourse rather than through everyday practice.

The global diffusion of Italian food introduced an additional layer of transformation. When Italian culinary practices began to circulate internationally, they encountered a fundamental constraint: complexity does not travel easily. In order to become recognizable, reproducible, and commercially viable across different cultural contexts, Italian food underwent processes of simplification, unification, and standardization. As John Dickie has shown, this reduction was not a betrayal of tradition but a functional adaptation that allowed Italian food to succeed on a global scale. Nevertheless, this process inevitably flattened regional distinctions and obscured the contextual logic that originally gave meaning to specific dishes and ingredients.

The success of this reduced version of Italian food has produced a paradox. On the one hand, Italian cuisine has become one of the most familiar and widely appreciated food traditions in the world. On the other hand, this familiarity often rests on a limited and homogenized understanding. For non-Italian audiences in particular, engaging more deeply with Italian food can appear to require technical knowledge, historical expertise, or detailed mastery of regional differences. In practice, this perceived threshold discourages engagement rather than fostering it.

This article proposes the concept of habitability as an alternative framework for approaching Italian food. Habitability does not seek to reconstruct total complexity, restore an imagined authenticity, or educate exhaustively. Instead, it aims to make diversity usable in everyday situations, allowing individuals to navigate differences without the need for expert knowledge. By shifting the focus from mastery to inhabitation, habitability offers a way to engage with Italian food that respects its plurality while remaining accessible and practical.

Italian food does not exist as a single, unified entity. What exists is a living plurality that has been partially reduced in order to travel beyond its original contexts. The challenge today is not to reject this reduction, but to move beyond it by developing forms of understanding that make complexity livable rather than burdensome.

References

Dickie, J. Con gusto. Storia degli italiani a tavola. Laterza, 2007.

Montanari, M. Il cibo come cultura. Laterza.

Montanari, M. (ed.). La cucina italiana. Storia di una cultura. Laterza.

Stay up-to-date